When Bengal: For generations, the sky has occupied a special place in the Bengali imagination. Dark monsoon clouds, the scent of rain on dry soil, and sudden downpours have shaped literature, music, cinema, and everyday life. Rain has never been just weather in Bengal; it has been emotion, rhythm, and memory. Yet, at a crucial moment in history, a group of Bengali scientists chose to engage with this emotional sky in a radically different way. They decided that clouds and rain would no longer remain only poetic metaphors. Instead, they would be examined through numbers, equations, experiments, and instruments. From that bold decision emerged one of the earliest Indian journeys into cosmic ray research and the scientific exploration of how rain is born.

Cosmic rays are high-energy particles that travel through space at speeds approaching that of light. Most of them are protons, along with nuclei of helium and other light elements. When these particles enter Earth’s atmosphere, they collide with air molecules in spectacular but invisible interactions. Each collision triggers a cascade of secondary particles, ions, and electrons, spreading through the atmosphere like a hidden shower. Though unseen by the human eye, these processes quietly influence the electrical and physical conditions of the air above us.

Bengali researchers were among the earliest in India to grasp that these invisible interactions were not merely abstract physics. They were deeply connected to the atmosphere itself. When cosmic rays create ions in the air, those charged particles can attract water vapor. Around these ions and microscopic dust particles, tiny droplets begin to form. These droplets are the earliest building blocks of clouds. As countless droplets merge and grow heavier, gravity eventually overcomes buoyancy, and rain falls. The key insight from this work was subtle but profound: cosmic rays do not “cause” rain directly, but they play an important supporting role in the earliest stages of cloud formation.

The challenge, however, was obvious. How does one study something that cannot be seen? The answer lay in a remarkable instrument: the cloud chamber. A cloud chamber is a transparent container filled with supersaturated vapor. When a charged particle passes through it, vapor condenses along its path, leaving behind a thin trail of droplets. For a fraction of a second, the invisible becomes visible. What would otherwise pass unnoticed is suddenly etched into space like a fleeting signature.

For Bengali scientists, the cloud chamber became much more than a laboratory device. It was, in effect, a piece of artificial sky brought down to Earth. Inside these chambers, cosmic particles traced delicate lines that revealed their presence and behavior. By studying those tracks, researchers could infer the energy, direction, and nature of the particles that had passed through. In doing so, they began to connect the physics of subatomic particles with the larger story of clouds, electricity in the atmosphere, and rainfall.

The deeper they looked, the clearer another fact became: the influence of cosmic rays increases with altitude. High above the ground, where the air is thinner, cosmic radiation is stronger and less shielded by the atmosphere. To truly understand these particles, measurements had to be taken not just on the ground but high in the sky. This realization led to one of the boldest phases of early Indian atmospheric research.

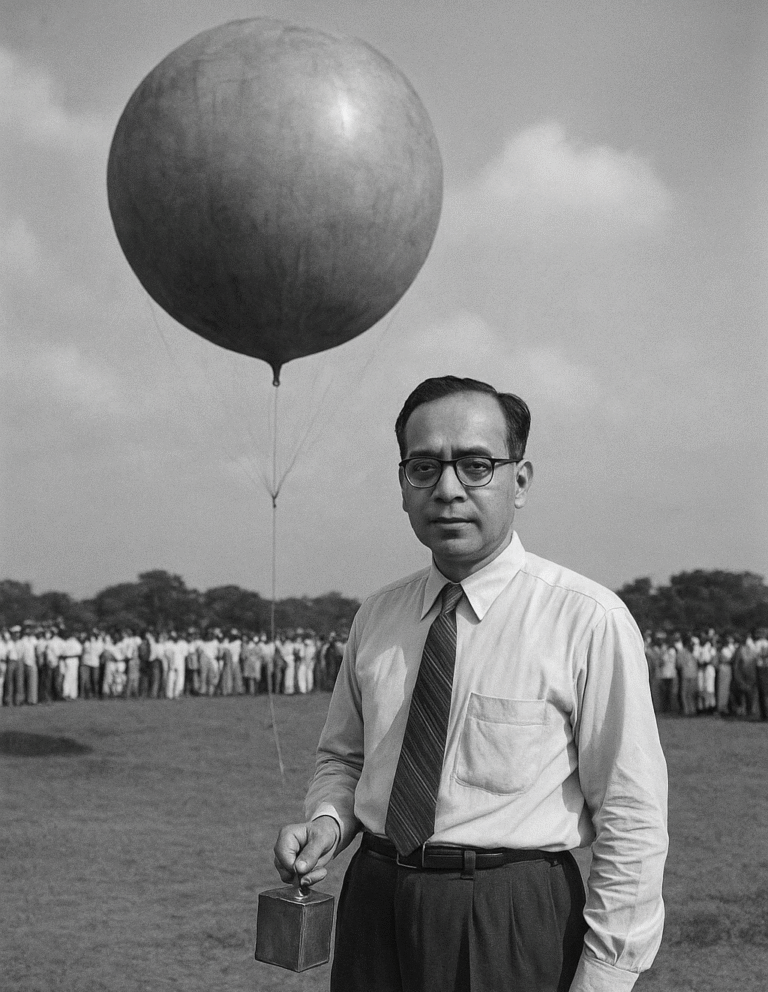

In the early 1950s, long before sophisticated research rockets were widely available, scientists turned to massive hydrogen-filled balloons. Beneath these balloons, they suspended delicate instruments, including cloud chambers and particle detectors. Designing such experiments required ingenuity and resilience. Instruments had to withstand extreme cold, low pressure, violent shaking, and the risk of total loss. Every flight was an experiment not only in physics but also in engineering.

As the balloons slowly ascended to altitudes of 15 to 20 kilometers and beyond, they entered regions of the atmosphere rarely explored at the time. There, cosmic ray interactions were stronger, and their tracks appeared with greater clarity. The data collected from these flights offered a diary of the upper atmosphere—records of ionization, radiation, and the invisible processes that shape clouds long before rain ever touches the ground.

Bengali physicists were not satisfied with merely measuring particle energies. They wanted to understand the broader implications. How did cosmic radiation affect atmospheric conductivity? How did ionization influence cloud electrification? Could these microscopic processes help explain lightning, storm formation, and rainfall patterns? These questions placed Bengali research at the intersection of particle physics, meteorology, and atmospheric science.

Among the scientists who earned international recognition for this work was Devendra Mohan Bose, whose experimental techniques in cosmic ray detection drew global attention. His work, alongside that of his contemporaries, helped establish a scientific tradition in India that viewed the atmosphere not as a passive backdrop but as an active, dynamic system shaped by particles, energy, and physics at the smallest scales. These contributions laid theoretical foundations that later generations of atmospheric scientists would continue to build upon.

From this growing understanding emerged a more ambitious idea: if the formation of clouds and rain followed physical laws, could humans influence the process under the right conditions? Around the world, this question led to the development of cloud seeding—the practice of introducing particles such as silver iodide into clouds to encourage droplet growth and rainfall. India, too, would later conduct experiments in various states, carefully analyzing humidity, temperature, cloud structure, and particle concentration to determine whether seeding could enhance precipitation.

Here, the intellectual connection becomes clear. Cosmic ray research demonstrated how tiny particles and ions can serve as nuclei for cloud droplets. Cloud seeding applied the same logic, replacing natural ionization with artificial nuclei. The message was not that rain could be commanded at will, but that it could be understood well enough to allow limited, respectful intervention. Rain was no longer purely mysterious; it was a phenomenon governed by probabilities, particles, and conditions.

Historically, it is true that the first documented successes of artificial rain occurred in Western countries. There is no reliable evidence claiming that a Bengali scientist produced the world’s first man-made rainfall on a specific date. Yet focusing narrowly on such a milestone misses the larger picture. The true contribution of Bengali scientists lies in their mindset. They were among the pioneers who believed that rain itself could be studied scientifically, not just observed or revered. Their early work on cosmic rays, atmospheric ionization, and cloud physics gave Indian meteorology a solid scientific backbone that earned international respect.

Today, as the world confronts climate change, droughts, floods, cyclones, and increasingly unpredictable monsoons, that early research has gained new relevance. Satellites, Doppler radars, and high-performance computers now allow scientists to map cloud systems in extraordinary detail. Yet beneath all this modern technology lie the same foundational principles—ionization, particle interactions, atmospheric physics—that those early researchers struggled to understand with far simpler tools.

This story, therefore, is not merely one of past achievement. It is also a call to the future. The same sky where Bengali scientists once traced the fleeting paths of cosmic particles may one day witness new, climate-friendly approaches to managing water resources. The dream is not domination over nature, but cooperation with it—using science to reduce suffering from droughts and extremes while respecting natural limits.

In that sense, the Bengali engagement with clouds and rain represents something larger than a chapter in scientific history. It reflects a cultural transformation: the decision to love the monsoon not only as poetry, but also as physics. And when emotion and inquiry come together, even the sky begins to share its secrets.

[…] Read More: When Bengal Looked at the Sky with Science: Cloud Chambers, Cosmic Rays, and the Quest to Understand… […]